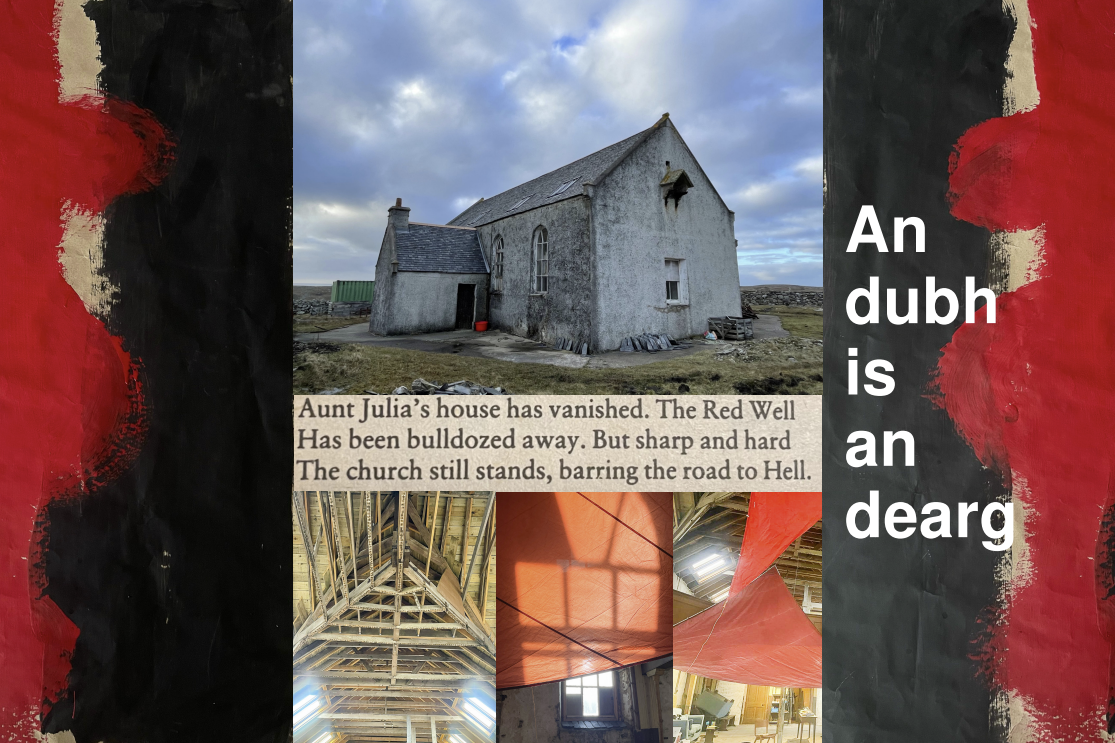

An Dubh is an Dearg - The Black and the Red.

Rupachitta Robertson

Artist winter residency at Baile na Cille and exhibition in March 2023.

Rupachitta Robertson

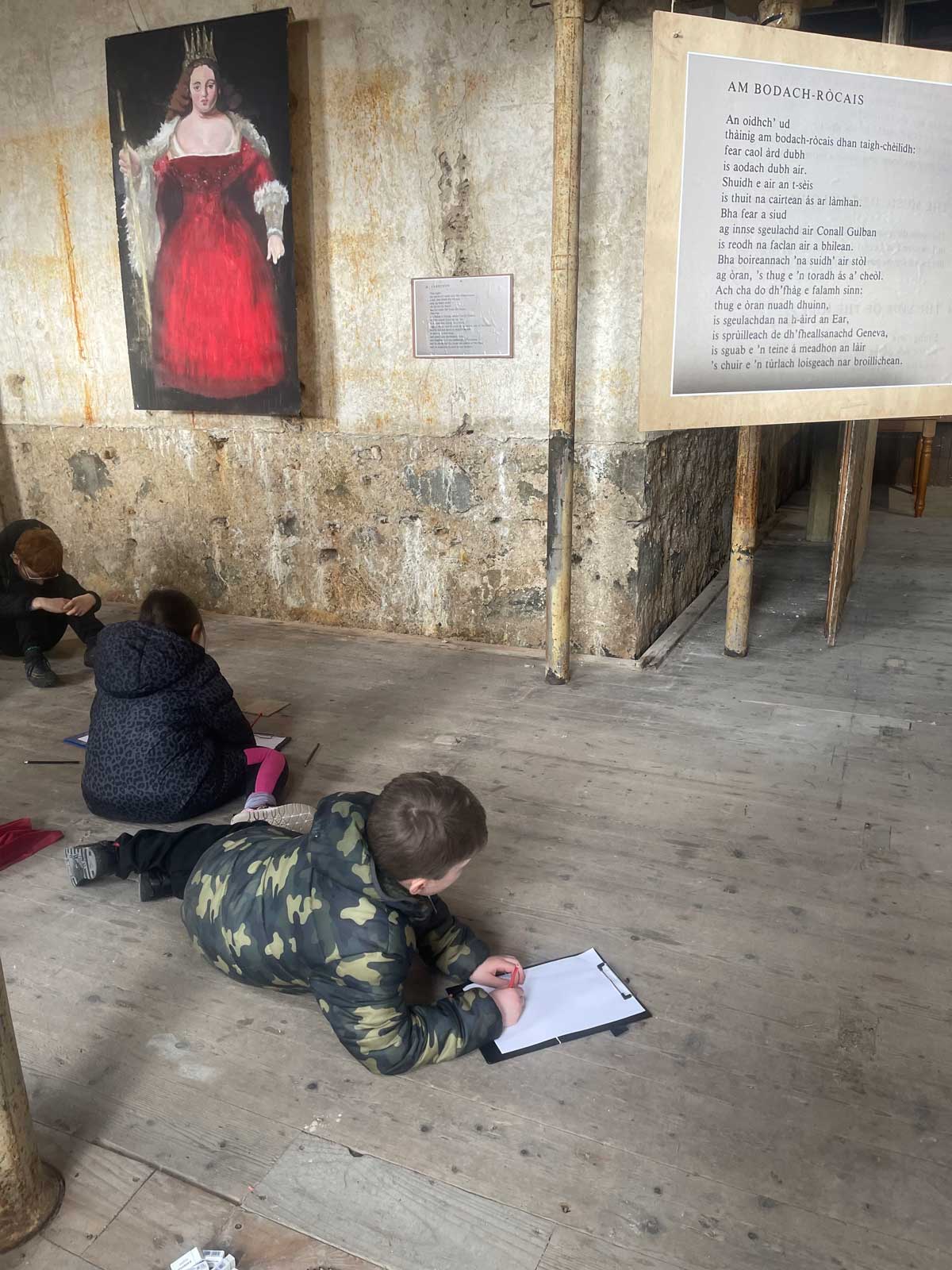

I had the use of Bailenacille church, Uig, Lewis for a working space in February and March 2023. The multi media installation gradually evolved as a response to the building and its history. This comprised large-scale paintings and assemblages of historic objects from local culture and handmade sculptural elements. A theme emerged about the impact of the Free Presbyterian Church on Gaelic culture and particularly on women. I drew inspiration from the poems Am Bodach Ròcais – The Scarecrow, by Derick Thomson and Return to Scalpay, by Norman MacCaig, as well as from the Gaelic praise poetry of the 16th 17th, and 18th centuries.

The exhibition that followed included also 3 large early 20th century red sails suspended from the interior of the roof, 4 large paintings inspired by strong Viking women, 4 very large (1.5x3M) paintings of red, leaping, naked women. Assemblages of Hearth and Floorbrushes, The Chairs, on which rested objects representing practices suppressed by the Church; prophecy stones, St Bridget’s crosses, a queens robe, a broken violin, a red dress, cards, chess pieces, wine cups. There was a collection of smaller paintings and a slide display of West side church buildings. The exhibition was accompanied by sound, including the recitation of the aforementioned poems.

Residency Story

In 2022, one of my drawings was runner up in the Highland Arts Prize. This was a huge affirmation and bolstered with a new confidence I wanted to break out of my tiny studio and work on a bigger scale. I asked if I could use the old church at Baile na Cille, Uig, Lewis. I had no idea what I wanted to do there, but I let the building and its history speak to me and gradually a momentum grew. The church was built in 1829 and was designed to seat a protestant congregation of 1000.

The first challenge was how to afford materials to work in such a large space. I thought I would try to get hold of old sails and cut them up for painting on. When I found a few, generously donated, and opened them up in the church, the colours and shapes were so lovely that I didn’t have the heart to cut them up. I had noticed that the ceiling of the (semi-derelict church) reminded me of looking into an upturned wooden boat. I wondered if the joiners who had roofed the church had also been Uig boatbuilders.

I hung the sails in the church and their deep red colours reminded me of the sails on my uncle Sandy’s boat The Veni. Some of my happiest childhood memories are of day trips in the Veni to one or other of the bays in Colonsay with my extended family.

Around this time I was asked if I would be interested in making an image/ sculpture of a female Norse woman for the Uig museum. I thought the two projects could be combined. I asked a colleague, whom I’d heard was into all things Viking and is a kick- boxing, surfing, powerful lady if she would pose for me. I took photographs of her, in her traditional red, Viking dress, with hammer and shield, on the brutal concrete plinths on the headland of Aird Uig, and started making drawings.

By this time I’d found the names scratched into the wood of the pews of bored children, long dead, who like me had sat through interminable sermons on beautiful days we would have much rather been somewhere else. Our Didòmhnaich’s or Latha na Sabainn, in Lewis Gaelic, were marked by restrictions; no games; no singing; no visiting cousins; definately no whistling and as little joy as possible!

The church, the sails, the strong Viking woman were working on me.

I was very fortunate to have had Iain Crichton Smith as my English teacher at Oban High School, a poet and writer himself, he had instilled in me a lifelong love of poetry and literature and introduced us to many of his contemporaries; poets working in English and Gaelic. Gaelic was my mother’s first language but like so many Gaelic speakers she hadn’t passed it on to her family. It had always bothered me that I couldn’t speak to my mother in her own first language. It wasn’t until 2000, after my mother’s death that I could go to Sabhal Mòr Ostaig and learn Gaelic. For the first time, I learned about the Highland Clearances, the Sea roads of the Saints, the treasury of Gaelic culture, and the sophistication of Gaelic poetry.

Ruairidh MacThòmais is a favourite poet and working in the church the words of Am Bodach Ròcais The Scarecrow came back to me

Am Bodach-ròcais

An oidhch' ud thàinig am bodach-ròcais dhan taigh-chèilidh

fear caol àrd dubh is aodach dubh air.

Shuidh e air an t-seis is thuit na cairtean as ar làmhan.

Bha fear a siud ag innse sgeulachd air Conall Gulban

is reodh na faclan air a bhilean.

Bha boireannach 'na suidh' air stòl ag òran,

's thug e 'n toradh as a' cheòl.

Ach cha do dh'fhag e falamh sinn:

thug e òran nuadh dhuinn,

is sgeulachdan na h-àird an Ear,

is sprùilleach de dh'fheallsanachd Geneva,

is sguab e 'n teine a meadhon an làir,

's chuir e 'n tùrlach loisgeach nar broillichean.

The Scarecrow

That night the scarecrow came into the ceilidh-house: a tall, thin black-haired man wearing black clothes. He sat on the bench and the cards fell from our hands. One man was telling a folktale about Conall Gulban and the words froze on his lips. A woman was sitting on a stool, singing songs, and he took the goodness out of the music. But he did not leave us empty-handed: he gave us a new song, and tales from the Middle East, and fragments of the philosophy of Geneva, and he swept the fire from the centre of the floor and set a searing bonfire in our breasts.

Ruaraidh MacThòmais, Creachadh na Clarsaich (Edinburgh, 1982), pp. 140-1.

The poem is a powerful indictment of the effect of the “philosophy of Geneva” i.e. Calvinism/ John Knox on Gaelic culture.

The words of another famous poet Norman MacCaig came back to me. “Return to Scalpay” is about Norman’s experience of returning to Scalpay, his mother’s native home.

“Aunt Julia’s house has vanished. The Red Well has been bulldozed away. But sharp and hard the church still stands, barring the road to Hell”

Iain Crichton Smith had pointed out to us scholars, how, with their steeples, the churches in England “point the way to heaven” but the Scottish church is “barring the road to hell”

It interests me that the difference of architectural styles indicates a difference in philosophical attitude also. I travelled up the West side of Lewis photographing the churches. Architecturally they are minimal, undecorated, the windows are screened or frosted so no one can see in or out. They look grim, austere, unwelcoming places. Lom is gruamach. I projected their images on the back wall of Bailenacille.

Initially, it was just the last sentence that I remembered but when I went back to look at the poem the previous two lines struck me. “Aunt Julia’s house has vanished” not only her house but a whole way of life.

“Aunt Julia spoke Gaelic very loud and very fast. By the time I had learned a little, she lay silenced in the absolute black of a sandy grave.”

“The Red Well has been bulldozed away.” The well/ tobar/ mot is a powerful symbol in Celtic culture, giver of water, life and wisdom, sacred to the old religion, they received prayers and ritual offerings. Here are the origins of throwing coins in wells and making wishes. We had to go to the well in Glassard, Tobar an Fhionn, in the summer when the water tank dried up, the well never did. The Red Well. An Tobar Ruadh. The well is named, it has capital letters, it would have been loved and feared.

One of Iain Crichton Smith’s books of short stories is called An Dubh is an Gorm, every story in it is a little masterpiece. The colours black and red kept recurring in my researches and so I called the project An Dubh is an Dearg, The Black and the Red. Black symbolizing the “the absolute black of a sandy grave”, the black uniform of the ministers, the darkness of winter nights- Dùbhlachd (December) na geamhraidh, the frightening times when food may be running out and the Wolf month (January), Am Faoilleach comes, the darkness of ignorance. Red on the other hands appears as The Red Well, blood, menstruation, fire and heat and conviviality and life and love.

I’d picked up a second hand art book in the local shop. I guess I’d known this, but it struck me forcibly how nearly all portrayals of women in Western art are of insipid, saintly, passive, simpering, or sexualised, brutalised, ugly, receptive women. Think!

I’d started a few images of a strong “Viking” woman about 1.5x 2 metres. A warrior with her sword, Huggin and Munnin; Thor’s ravens from Norse Mythology, in the sky above her. A moon pointer grasping a snake. A queen, based on Rembrandt’s Juno. Gradually, my paintings moved from images of strong Viking women, to a Queen, and then to wild, dancing, red, naked women. I bought rolls of heavy, strong, Fabriano paper and used acrylic paints, in increasingly large, 2.5m x 3.5m, pared down images.

Meanwhile I’d started thinking about the way, in Thompson’s poem the Scarecrow “came into the ceilidh house and swept the fire away from the centre of the floor. One of the most enduring tropes of Gaelic poetry is the Taigh nan Teud, the House of the Clarsach, the house of music. The Bàrds (trained poets) were traditionally, second in power to the clan chief. They were respected and feared as they held the ability to praise or blame for posterity, the reputation of the chief. They were the newsmen and women of the day.

Traditionally the chief was evaluated according to how good was his hearth, his hospitality, his wine, musicians, food and entertainment, his physical elegance and his bravery in battle. These traditional practices, of hospitality, the second sight, storytelling, pagan rituals and votive offerings, were all swept aside by the protestant church.

I was gathering objects that represented the things that the poem The Scarecrow tells us were swept away when the tall, thin black haired man, wearing black clothes came into the ceilidh house, the traditional seat of hospitality of the Gaels. In traditional black house homes, the fire was in the centre of the house both physically and metaphorically. Not only was food prepared there but it provided heat and a focus for social gatherings.

In pre-television Gaeltachd, extended family and neighbours would gather round the fire, exchange news, sing a song, maybe there was a fiddler or piper present to add to the ceilidh. The old stories, going back hundreds of years and shared with the Irish Gaeltachd would be recited.

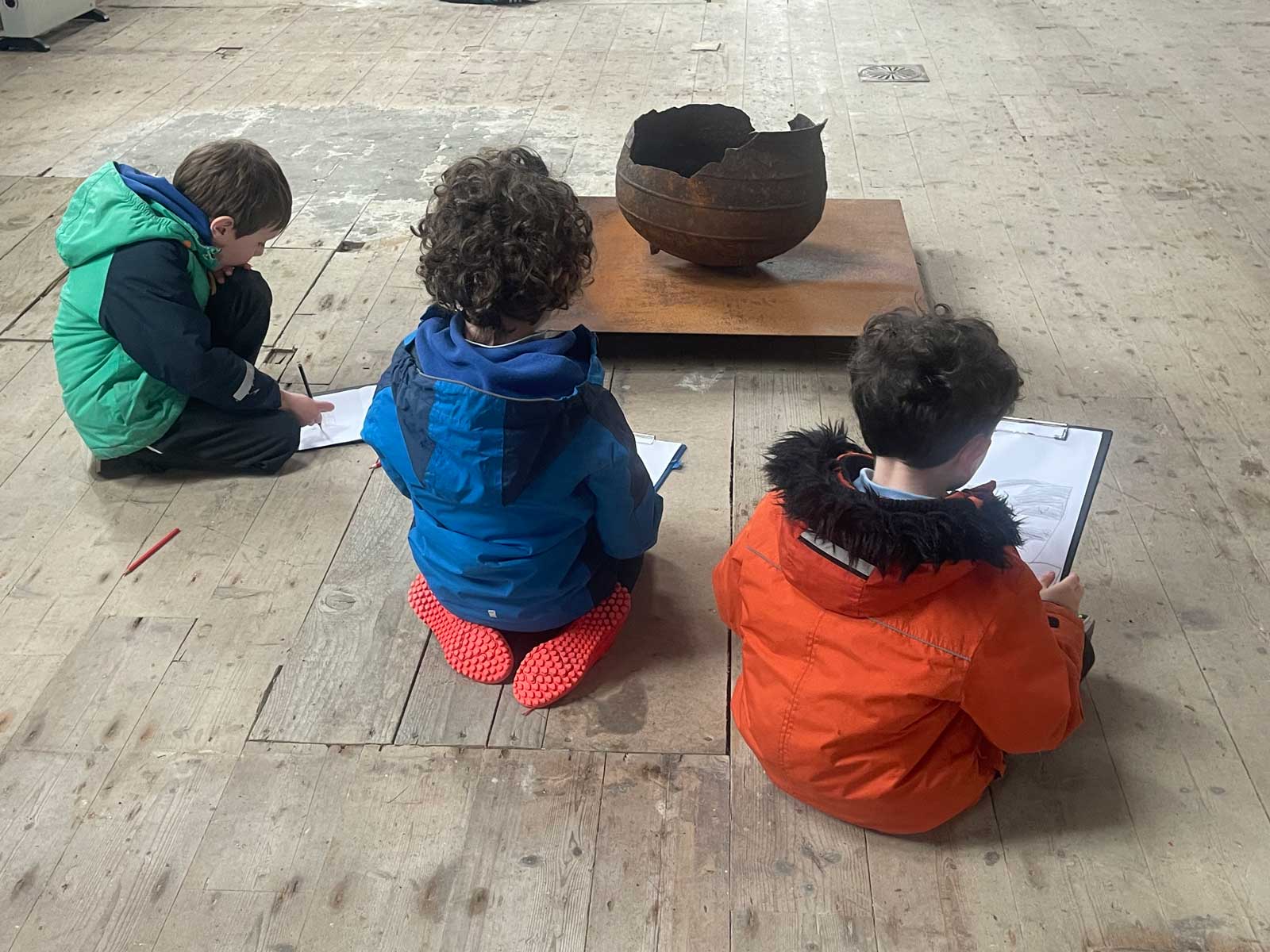

I constructed a hearth in the middle of the church, I made floor brushes to symbolise the sweeping away. When the exhibition opened many people referred to them as a cauldron and broomsticks, immediately associating these humble, domestic, (female) objects with witchcraft. What does that tell us?

In the course of my research I came across Professor Donald Meek’s critique on The Scarecrow “instead of the collective solidarity of a Gaelic community. The scarecrow displaces that solidarity, symbolised by the fire; he kills off what is good within the culture, and substitutes one set of stories and songs for another” “Culture is given a new orientation; in fact, an alien culture is brought in from Geneva and the Middle East. More ominously, the scarecrow destroys the collective conscience of the community, and puts the weight of responsibility on the individual conscience; the fire, once a focal point of warmth, assumes a destructive, rather than a constructive, role.”

I also discovered how John Knox, “a tall, thin black-haired man wearing black clothes.” Scotland’s own fanatic Calvinist and notorious misogynist had published in 1558, and preached “The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women.” It attacked female monarchs, and any authority that women might hold, arguing that rule by women is contrary to the Bible and a violation of the “divine and natural order of the world”. Mary Queen of Scots was a catholic and Knox believed that as queen she would restore Catholicism and burn protestant heretics, following the example of Bloody Mary Tudor. Knox would eventually advocate and agitate for Mary, Queen of Scots’ execution.

I asked a friend who is a devout Free Presbyterian, whom I regard as a hardworking and exemplary secondary teacher, why she doesn’t train for the ministry. She was aghast that I could even suggest such a thing.

The Chairs two circles of four chairs each with objects on them which represent different aspects of traditional Gaelic society that were suppressed by the church.

The Clachan Nathraich of Coinneach Odhar, the stones with holes in them through which the Brahan Seer made his prophecies. Second sight was not regarded as being particularly unusual in Gaelic society, just as most villages would have had a Bard, so too, there would have been story tellers, seers, genealogists. My own mother was a seventh daughter and as such, grew up, believing that she would have that particular ability of second sight.

The Broken Fiddle -music of any kind is frowned on by the Free Church, the fiddle has for centuries been regarded as the work of the devil, inciting people to dance and frolic. It was only in 2010 that the Free Church of Scotland voted to allow the singing of hymns and musical instruments in its churches.

“We don’t countenance flowers in our church” as I was told when offering to do flowers for the funeral of my ex-partner’s mother.

The red velvet Queens robe edged with ermine. Rembrandt’s painting of Juno has been an inspiration for many years. She is a mature woman with a full figure, she wears a golden crown, her right hand rests lightly on a sceptre, her face has a subtle smile and her eyes look directly at us. There is a deep stillness, confidence and strength about her. Her left arm hangs down and it is impossible to make out what she holds in her left hand. The last act of my residency was to paint a rosary in the hand of The Queen.

The Red Dress symbolising unashamed, female sexuality. “Women who put on men’s clothing are breaking Old Testament law, states the (Free Presbyterian) Church, which recently rapped those (women) who go to church without a hat”

Dice, chess board and pieces, wine and drinking cups. These all feature in the òrain mholaidh, the praise poems of the Gaelic tradition.

The Croisean Bhrìghde. The Bridget’s crosses, Bridget was a saint of the Celtic church and probably a pre-Christian figure in Celtic mythology. A patron of fertility her crosses would be made on the 1st of February or Imbolc, marking the beginning of Spring. Oystercatchers are known as Gillean Bhrìghde – Bridgit’s boys or servants. If you listen to their call you will hear Gille-Bhrìghde, Gille-Bhrìghde. Bridgit’s name appears in many places as Cille Bhrìghde- Kilbride.

As you leave the exhibition, in front of you is a reproduction of a photo of the Winged Victory of Samothraki, dating from the 2nd century BCE, the original is now in The Louvre. When I was a student at Glasgow School of Art, a plaster copy of the Victory was mounted above the entrance stairs. It soared above us, beckoning us to emulate the soaring freedom and grace of her forward moving body.

I would like to thank Andy Laffan for his encouragement and Brian and Miranda Gayton for the use of Bailenacille church.